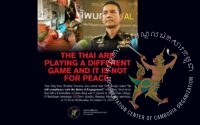

Thailand, Cambodia, and a Competition Over Territory and History.

There are several misconceptions of the recent conflict between Thailand and Cambodia that have implications at the local, regional and global levels. The conflict is not new, insignificant or localized. And, unless this conflict is resolved appropriately and soon, the impact of this conflict has the potential to reverberate across the region and the world.

In many ways, this conflict represents the next iteration of a centuries-old Thai nationalist sentiment to reclaim territory lost to Cambodia and unfair Western colonialism. This Thai nationalist sentiment is rooted in the history of the shifting borders between Cambodia and Thailand.

For centuries, the areas of Battambang, Svay Sisophon, and Siem Reap were controlled by the Kingdom of Cambodia. In 1795, these areas came under the control of Siam (modern day Thailand) as a result of infighting within Cambodia’s Khmer nobility. As a consequence of Cambodia’s weakness and in exchange for placing a Cambodian prince on the throne, Siam absorbed these areas of Cambodia.

Under pressure from the French who took Cambodia under their colonial protection in the 19th century, these areas were returned to Cambodia in 1907, and between 1907 and 1941, France managed these areas as part of the Cambodian territory of French Indochina. Hardly a coincidence, in the same year that Cambodia reclaimed its northern and western provinces from Siam, Cambodia suffered what was reported as Thai-sponsored banditry in the Battambang and Anlong Veng regions. These attacks, which might be characterized today as “grey zone warfare,” arguably foreshadowed Siam or modern-day Thailand’s long struggle to recover what it perceives as its territory—territory that contains many ancient religious temples and cultural sites dating from the Khmer Empire.

In the wake of France’s defeat by Nazi Germany, Cambodia lost French protection in 1941, and Siam took control of Battambang, Svay Sisophon, Siem Reap, Stung Treng, and Kampong Thom (including Preah Vihear and Preah Vihear temple). Siamese control over these areas, however, was short-lived. With the Allied powers’ victory in World War II, in 1946, the United States forced Siam to return those areas lost in 1941 to France and Cambodia. The treaty returning these areas was signed on November 17, 1946, in Washington, D.C.

When Cambodia gained independence from France in 1953, Thailand continued to dispute its border with Cambodia, arguing that it was unfairly imposed under colonialism, particularly around the Preah Vihear temple. In 1954, Thai troops occupied the Preah Vihear temple, prompting Cambodia to bring the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The ICJ ruled in 1962 that the temple was situated in Cambodian territory, and in 2013, the ICJ reaffirmed Cambodia’s sovereignty over Preah Vihear.

Since 2013, periodic skirmishes occurred over the border, until 2025, when major clashes erupted causing casualties, massive civilian displacement, and the threat of war between the countries.

Between May and July 2025, severe fighting erupted along multiple sections of the border between Cambodia and Thailand. The violence displaced over 300,000 civilians and involved air strikes, artillery exchanges, and accusations of violations by both sides. At the initiative of United States’ (U.S.) President Donald Trump, a ceasefire was reached on July 28, 2025, which was managed by Malaysia and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Importantly, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) also came in to support the ceasefire.

The conflict, which continues to simmer despite the ceasefire, is not a temporary dispute that is isolated between the two current governments and their militaries; rather, it is substantially based on strong opposing views of history.

Thailand’s historical and current attempts to occupy Cambodian border regions can be described as “revisionist expansion.” This term reflects Thailand’s efforts to reinterpret historical boundaries and expand territorial control based on nationalistic and revisionist interpretations of colonial-era maps and treaties. Thailand’s revisionist expansion is partly informed by a view that Western colonialism interfered with Thailand’s “legitimate” national expansion; however, it is also shaped by national security concerns.

The Thai government views Cambodia as a potential threat to its borders and its domestic security. Officials have cited Cambodia’s alleged role in facilitating transnational crime networks, scams, and illegal migration as justification for tightening border controls across Cambodian-border provinces and increasing military oversight of crossings. The United States’ recent indictment of Chen Zhi, the founder and chairman of Prince Holding Group (Prince Group), a multinational business conglomerate based in Cambodia, for, among other charges, forced-labor compounds across Cambodia is one case in point of Cambodia’s ongoing struggle with criminal syndicates operating in the country. But the Thai authorities’ national security concerns are only one matter (that is arguably pretextual) among many others contributing to Thailand’s growing need to expand its territory and sphere of influence.

According to an August 2025 Ipsos survey, 86% of Thais expressed concern about the border escalation, and military conflict became the nation’s top worry, surpassing corruption and poverty. The conflict with Cambodia may have been instigated by legitimate national security concerns, but it also appears to be perpetuated as a means to distract public attention from other internal issues and to refocus attention to nationalist and even militant views of the direction of the nation. In the face of a foreign threat, people are not only naturally inclined to look to their government and military as their protector, but they are more easily manipulated to accommodate whatever agendas align with an “us versus them” perspective. As U.S. President Trump has stated, “Anyone can make war, but only the most courageous can make peace.”

But making peace may not be in the Thai military’s actual interests. Historically Thailand has struggled with ensuring civilian control over its military. According to multiple sources, Thailand has had at least 13 successful military coups, and 22 coup attempts since the end of its absolute monarchy in 1932. Some experts believe the country has normalized the practice of using a military coup to reset or restore political order, and to no small extent, the border dispute with Cambodia may be more important as a tool for the military than it is a dispute that Thailand sincerely seeks a peaceful solution.

But peace is really the only option for both countries and the region because any escalation of force is guaranteed to produce losers on all fronts. To this end of securing peace, there is a misperception of the extraordinarily high stakes for the region and the world should this conflict escalate or even persist in its current form. There are three major implications this conflict has for the region. First, the escalation or persistence of this conflict all but guarantees the erosion of ASEAN unity. A house divided cannot stand, and the conflict will inevitably weaken, if not significantly impede, ASEAN’s economic, developmental and political objectives. Second, this conflict has already caused substantial cross-border economic disruption, and as the conflict persists, there will be immeasurable impacts on long-term economic development of both countries and the region. Finally, there has already been significant humanitarian impacts of displaced people. As the conflict simmers, migration pressures will also continue, causing potentially cascading effects across the multiple inter-related social, economic and infrastructure systems in one or both countries. While all of these issues are extremely important for the region, I want to focus on the implications for world affairs.

There are two major implications this conflict has for the world: (1) The magnification of U.S.–China rivalry; and (2) The further degradation of international law.

Currently, Cambodia treads carefully between an economically robust friendship with the PRC and an increasingly friendly relationship with the United States. Thailand, on the other hand, is navigating its historical relationship with the United States in the context of an increasing nationalism that demands bolder military action. Though past foreign policies and relationships are not guarantees of future strategies and partnerships, it is not hard to see how the continuation of this conflict risks the magnification of ongoing strategic competition between the United States and China.

Furthermore, any disregard for an international court ruling like the ICJ weakens international law. Bilateral mechanisms for communication and the resolution of disputes are important, but they should not completely replace the judgments of international institutions like the ICJ.

U.S. President Trump stated in January 2025 that his proudest legacy will be that of a “peacemaker and unifier.” Recalling the United States’ historical role in securing peace in Southeast Asia and throughout the world in the wake of World War II, the time for peace is now between these two Asian countries.

—–

Youk Chhang is the director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), established in 1997 as an independent, non-governmental Cambodian civil society organization dedicated to justice and memory. Chhang is a recognized leader in genocide education, prevention, and research. In 2018, Chhang received the Ramon Magsaysay Award, known as “Asia’s Nobel Prize,” for his work in preserving the memory of genocide and seeking justice in the Cambodian nation and the world. In 2007, he was nominated as Time Magazine’s Top 100 men and women. Chhang has worked with civil society organizations and leaders around the world, including Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Myanmar, and other post-conflict developing countries. He is currently building upon DC-Cam’s work to establish the Sleuk Rith Institute, a permanent hub for genocide studies in Asia, based in Phnom Penh. Pursuant to this goal, in 2020, DC-Cam established the Queen Mother Library, named after Queen Mother Norodom Monineath Sihanouk. The Queen Mother Library (Museum-Institute) holds the world’s largest, rare archive of historical artifacts and documents of the Khmer Rouge regime, many of which have been used to support the work of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC).